In the midst of quarantine and confusion, there’s a real temptation to look only forward—to tomorrow, next week, next year, when surely, everything will be “better,” or “back to normal,” or simply “safe,” whichever is your fantasy of choice. But a better tomorrow can’t come unless we pursue it with intention and wisdom, and to do that, we need to turn around and examine the lessons of the past.

Have we ever experienced a pandemic at the scale of this novel coronavirus? Not in most of our lifetimes, no. But that hardly means the past is devoid of clues for how to proceed, succeed, and thrive. Specifically, it’s valuable to look at times of past recession for inspiration in this era of perilous financial straits. How have companies approached various aspects of their business plans during previous periods of belt-tightening, and what tactics have worked better than others?

Ninety years ago last October, the United States entered what would come to be known as the Great Depression, precipitated by Black Tuesday, the stock market crash on Oct. 29, 1929 when the Dow fell by 11.73 percent, after having already lost 11 percent on Oct. 24, Black Thursday, and 12.82 percent on Black Monday, Oct. 28. The Great Depression, which lasted nearly a decade, saw a worldwide GDP drop of 15 percent and a U.S. unemployment rate of 23 percent.

By comparison, the effects of COVID-19 have put our U.S. unemployment rate hovering just over 20 percent, with current forecasts predicting a drop in the worldwide GDP of perhaps as much as 2.4 percent. But, with the stock market scare a couple of months ago that saw a drop of 10 percent, many companies are assessing their situation, making hard decisions, and looking for a path forward.

One of the most famous tales in marketing is that of Kellogg’s vs. Post. It’s the kind of lore that seems apocryphal the first time you hear it, but it’s genuine and true, and it’s the best example of the advice from the past that companies of today should be seeking.

Kellogg’s was founded in 1906, Post in 1895, both in Battle Creek, Michigan. They were close rivals during the early part of the last century; C.W. Post had actually been a patient at the sanitarium run by John Harvey Kellogg. Together, they were the dominant names in ready-to-eat breakfast cereal. Their trajectories were roughly comparable in terms of popularity … until the Great Depression hit.

Post saw the risk on the horizon, and the company turtled. It made all of the choices that anyone looking only forward would think were logical and reasonable. It cut costs, it pulled back on spending, especially on something often considered ancillary: advertising. And it worked, for what it was worth. Post survived the Great Depression intact; after a series of mergers, renaming, and breaking back apart, they’re still here: Their flagship cereal, Grape-Nuts, now 123 years old, is still sold and eaten.

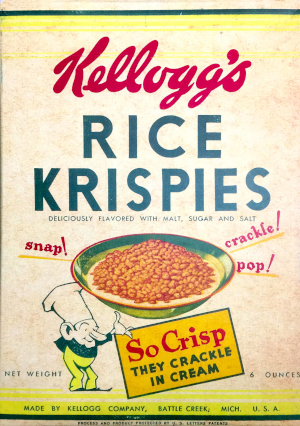

A 1930s-era box of Kellogg’s Rice Krispies. — user Smash the Iron Cage, CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

But Kellogg’s didn’t just survive: It became a success story. It’s now the top-selling U.S. cereal company (though General Mills’ Honey Nut Cheerios regularly beat out any of its specific offerings for top-selling cereal). It holds over 30 percent of the market share. And its success can be directly attributed to the product that it developed and aggressively marketed when its peers were all playing their cards close to the vest: Rice Krispies.

Rice Krispies was launched in 1928, just before the Great Depression hit. With such a new product, it would have been easy for Kellogg’s to hold back and avoid risk. But they persevered instead, leaning hard into their new product—and specifically into the advertising of it. The novel “snap, crackle, pop” sounds the cereal made were a hit on radio advertisements, and the gnomish onomatopoetically named mascots designed by illustrator Vernon Grant still grace the box to this day.

Kellogg’s wasn’t the only company to bet on success when others were holding back during the Great Depression. Chrysler took that chance to release its Plymouth, and in 1933, it overtook Ford to make it to number two (behind G.M.) in the U.S. auto industry because of it. Kraft introduced Miracle Whip in 1933 as well, to great success.

Advertising isn’t a luxury; it’s an investment. And companies that are wise enough to learn from the past—rather than staring, blindered and hopeful, at an uncertain future—will be rewarded for their innovation, perseverance, and smart marketing. We’re all in this together. Bankers is here to support and spin success off of creative ways to reach out and stay, always, relevant and compassionate. Take a chance—your customers will rally around you.